Have you ever wondered why the Palghar Sadhu Lynching incident didn't kickstart a mass movement of protest but the death of a 34-year-old actor did? Again, simple: It had nothing to do with "Oh Hindu Sadhus therefore ignored" (though that was definitely there), but the heinous, cold-blooded, long-in-the-making and utterly, absolutely ruthless manner in which a celebrity with a boy-next-door image was surrounded by a group of rich and powerful and pushed to a dark corner from which there was no escape except a long last fall over the edge into oblivion, and subsequently the media-police-politician-bollywood-underworld nexus that worked like a scarily well-oiled machinery to hush up the case, which reminded the country about the Dec 2012 atrocity in Delhi and roused the nation's collective conscience. It was, simply put, a question: "If such a terrible thing can happen to Sushant, then what hope do we commonfolk have?" It was a repeat act of the question that the country had asked itself at the time of Nirbhaya. This time, it was Sushant.

A major, major clean-up of the viper's den that bollywood has become has been overdue. Anyone not conforming to the rules is given a gentle push over the edge, a figurative hand in the back, and the rest is taken care of police investigations that find nothing suspicious, politicians who orchestrate their cadres in the guise of supportive fans, and media stooges who already have shiny, spanking-new clean chits out and waving in the air, pouring the milk of "child in a man's body" and "so much humanitarian work" and "weeps when he hears a 'lori' song and has to be consoled by his mum" on the blood of innocents dripping from the hands of the khans, the bhatts, the kapoors and the johars. Divya Bharti and Sridevi were drunk, Jiah Khan and Sushant and Parveen Babi were depressed... Same screenplay, different victims.

And this is where the secret of their escape route lies: the ability to orchestrate a whitewashing-and-hoodwinking campaign that has us eating out of their hands time and time again. We will forget all about Sushant the moment the next bachchan / srk / salman / ranbir kapoor film hits the theaters because to us, celebrating the glory of our stars who care two hoots about us matters more than innocent lives nipped in the bud in the most monstrous manner possible and justice and punishment...until the next dead body appears, hanging from the ceiling or drowned in a bathtub.

But remember one thing: the next guy or girl who falls victim to these hungry predators coming out of the scummy cesspool of unlimited power could be someone you love. I hope your breathless anticipation of the next bachchan / srk / salman / ranbir / deepika movie remains the same at that moment of utter despair.

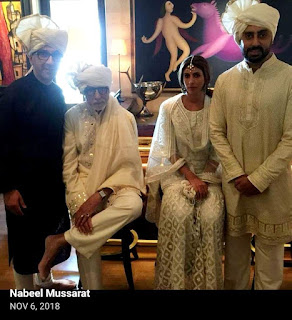

P.S.: Here are some snaps of bollywood's A-listers with brothers Annel Mussarat and Nabeel Mussarat, two of pakistan's richest and most powerful businessmen, who often act as go-betweens between pakistan's ISI and the rich and the famous, esp of the Indian variety.

"Nothing wrong in being clicked with some businessmen, even if they're from pakistan," you say? Well, do remember that that is exactly how dawood ibrahim had dug his tentacles deep inside bollywood in the 1980s.